Text: Anders Rydell, FARM #5 2011. (Translated from Swedish)

The small water fern Azolla can do almost everything, replace chemical fertilizers, serve as food, prevent malaria and pave the way into space. Perhaps it is also responsible for the Earth’s climate.

I’m standing outside a uniformly gray apartment building in the Stockholm suburb Årsta in the worst winter cold in decades. It is a boring house to look at. Nothing here would interest me if I didn’t know what was hidden in the basement. There grows something which probably has had an impact on all of our lives.

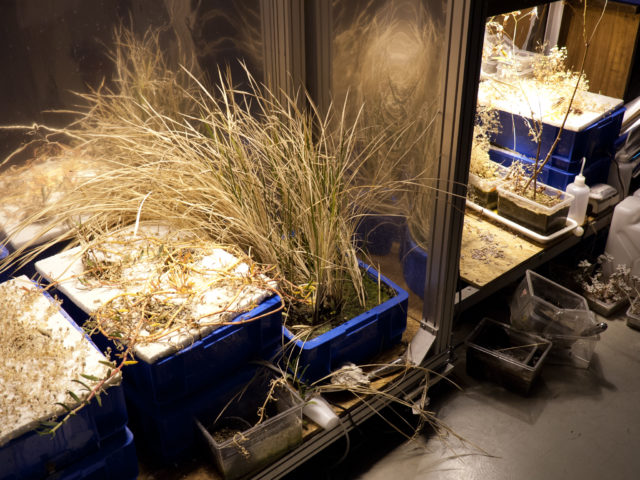

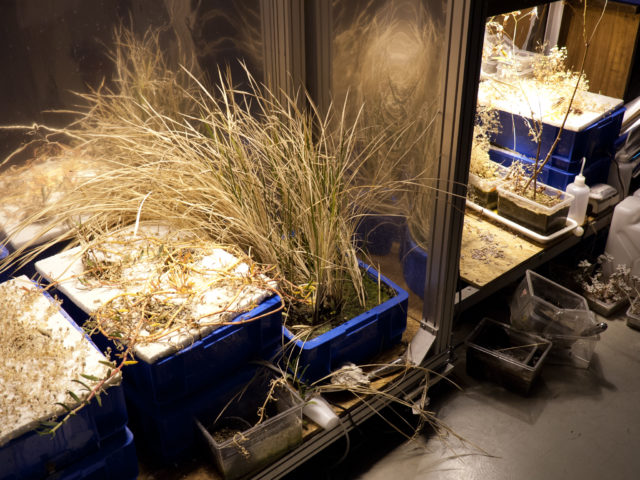

[Azolla cultivations in Årsta. Photo: Erik Sjödin.]

By the door I meet the artist Erik Sjödin. He has a scarf wrapped tightly around his neck. He sniffles and invites me into a small room that can’t be more than 20 square meters. He tells me that he rents it for 800 Swedish kronor a month and hands me a cup of tea. It’s buzzing from fluorescent lights and bubbling from pumps. In ten or so rectangular plastic boxes floats a plant that Erik has become virtually possessed by, a plant which has been attributed almost miraculous properties. Azolla is a moss-like water-floating fern that has fascinated space scientists as well as rice-growing philosophers. This extremely nutritious plant has been used both as fertilizer and animal feed. Its special properties has also made it interesting for agriculture in space. But through his project “Super Meal” Erik Sjödin explores another use, Azolla as a future food.

– It tastes a little like forest, mossy, but if you spice it up and fry it it tastes OK, says Erik.

[Azolla food cooked at Färgfabriken. Photo: Erik Sjödin.]

The ongoing project has resulted in several exhibitions and in the future it will become a book. Actually Azolla doesn’t belong in Årsta but in the tropics. It is obvious that it doesn’t really thrive in a basement. Erik says he is only trying to keep the plant alive until the winter is over. In the boxes floats more or less thriving Azolla, from healthy green to decaying brown. For safety’s sake he has applied different methods of cultivation in the boxes, some are filled with peat and fertilizer, others with topsoil. All in an attempt to find the best conditions.

– It seems to be surviving now, but it’s nothing compared to how it grows in the summer. I planted it in a pond at the art and farming collective Kultivator on Öland last summer. It filled up an area of perhaps 50 square meters in a few weeks, says Erik.

Under the right conditions Azolla isn’t difficult to charm, it is the fern’s unique symbiosis with a bacteria that makes it grow so fast that in many parts of the world it is considered the worst of weeds. Under ideal conditions Azolla can double its biomass in just two days, making it one of the worlds fastest growing plants.

Erik Sjödin’s love affair with Azolla began in late 2009 when he visited a friend who carries out research at the Department of Botany at Stockholm University.

– They grew Azolla in a greenhouse. It was really green and thick, like a lawn. When you touched it the whole surface rippled, I was caught by the aesthetic qualities. Then I thought that I must do something with this plant.

Erik began reading about the fern, and found among other things a recent report from Japan’s equivalent of NASA, JAXA. The report pointed out Azolla as a key crop for a possible colonization of Mars, but he found no recipe for how to cook it. So he decided to try it out himself.

[Azolla and rice cultivation at JAXA. Photo: Erik Sjödin.]

The experiments did, among other things, result in an exhibition at the art space Färgfabriken in Stockholm during the summer of 2010, where Erik together with Färgfabriken’s cafe came up with several dishes using Azolla as an ingredient. Among other things Azolla burgers and Azolla soup. During the fall Erik Sjödin visited the researcher Masamichi Yamashita at JAXA outside Tokyo, who had written the report on Azolla. Yamashita’s research area is space agriculture. In addition to research on Azolla he has, among other things, done research on silkworms as a source of proteins on Mars.

– The goal of space agriculture is to grow as much food as possible with the least amount of resources. It is the most efficient farming you can imagine. Everything must be done in completely closed systems with animals and plants. It is extremely difficult to achieve.

Erik gives me a book with recipes from the Biosphere 2 project. A result of an experiment where a number of scientists were locked in a closed system in Arizona for a few years in the nineties. In the project Azolla featured as an important crop.

– Through his research Yamashita has figured out that if you create a system where you grow rice, Azolla, fish and insects you could produce all the food that a person needs to survive on a surface that is less than 200 square meters, says Erik Sjödin.

To put it in perspective, the average American diet now require 21 000 square meters per capita, 105 times more than the Azolla system.

What makes this little water fern so special is its energy content. Dried Azolla contains 25-35 percent protein. In addition it contains a slew of minerals, vitamins, amino acids (a total of about 20 percent dry weight). Nutritionally it is comparable to alpha-alpha sprouts and algae such as Spirulina.

However, what makes Azolla unique is its nutrient content in combination with its rapid growth ability. The Azolla live in symbiosis with a so-called cyanobacteria (Anabaena Azollae). In the Azolla’s upper leaves there are small cavities in which these bacteria grow. The fern provides protection for the bacteria while they are nitrogen-fixing, which makes it possible for the Azolla to get nitrogen both from the air through the bacteria and from the water through its roots. This dual energy system provides the fern with a kind of biological turbo engine.

The high energy content and the propagation speed makes Azolla ideal both as a nitrogen fertilizer and as fodder. This has not been entirely unknown, on the contrary Azolla is mentioned in Chinese literature as far back as two thousand years ago. In a book about farming from the sixth century it is described how Azolla can be used as fertilizer in rice cultivation. By growing Azolla in rice paddies a natural fertilization process is created. However, Erik says that the tradition of using Azolla as natural fertilizer has been lost in many locations.

In various parts of the world Azolla has long been in use as animal fodder because of its nutritional content. But according to Erik Sjödin there is a wide range of further uses of the plant which has been nicknamed “A Green Gold Mine”.

– It could for example be used in water treatment systems because it is very good at absorbing heavy metals from water. Another application that has been talked about is malaria prevention, Azolla forms an extremely dense cover on water surfaces which is said to prevent the reproduction of mosquitoes. Azolla as biofuel and medicine has also been discussed.

But research on climate history at Utrecht University in Holland suggests that Azolla probably has played a much more significant role throughout our history. 49 million years ago, scientists believe a massive bloom of Azolla at the Arctic (which then was a warm sweet water ocean) fixed so much carbon dioxide from the air that it changed the Earth’s climate. The bloom is supposed to have carried on for 800 000 years and cooled down the Earth, which was much warmer then. In other words, Azolla created the climate we know today. Within the sciences the event has become known as “The Azolla-event”.

We leave Erik’s green basement room in and step out into the cold. Erik says that it is important that the use of Azolla in for example agriculture isn’t perceived as a return to something “primitive” – but as something progressive. He sees a risk in that people perceive this type of solutions as a step back, to something “natural”, instead of something more advanced than the agriculture we have today and have had in the past. Through the project he wants to pose questions about how we approach agriculture and food production.

– Agriculture, for example rice cultivation, is based on monocultures today. There is only room for one crop, and everything is driven by machinery, chemical fertilizers and pesticides. It works, but it isn’t sustainable in the long run for many reasons. But by designing systems in which several animals and plants interact, it is perhaps possible to create an agriculture that is both more sustainable and more productive.

However, Erik doesn’t want to be perceived as an Azolla prophet.

– I have no definite answers. I just want to raise the question whether another system is possible? I have been contacted by everything from small scale farmers in India to horse ranchers in the U.S. who want to use Azolla in various ways. I want to disseminate knowledge, but it is important not to create any illusions that this plant is a panacea. It’s important to tread forward carefully, if you release Azolla in the wrong environment it can cause serious problems.