Interview w/ Regine Debatty. We Make Money Not Art, 2018:

Erik Sjödin‘s art and research practice has led him to investigate human relationships to fire, aquatic plants that might one day feed the first inhabitants of planet Mars, bees and humans connections and community-based ways of producing food.

[Erik Sjödin, Bee shed in Lötsjön natural reserve and park, Stockholm, Sweden 2018. Photo: Erik Sjödin.]

I’ve been following his work since 2011 and always thought there was something remarkably peaceful, generous and efficient about his work. At a time when artists, journalists and scientists alike are calling for a more considerate, a less anthropocentric way to live on this planet, Sjödin is quietly doing just that. Working on potential solutions to problems of contemporary urgency and sharing the lessons with others through exhibitions, publications, workshops as well as collaborations with scientists, farmers, gardeners, other artists and chefs.

Anytime is a good time to catch up with Sjödin and interview him about his latest projects. My excuse to get in touch with him again is Community Services, an exhibition in Marabouparken in Sundbyberg, just north of Stockholm. The show brings human beings closer to bees by revealing how the small pollinators have been “understood, written about, cared for, neglected and persecuted by humans.”

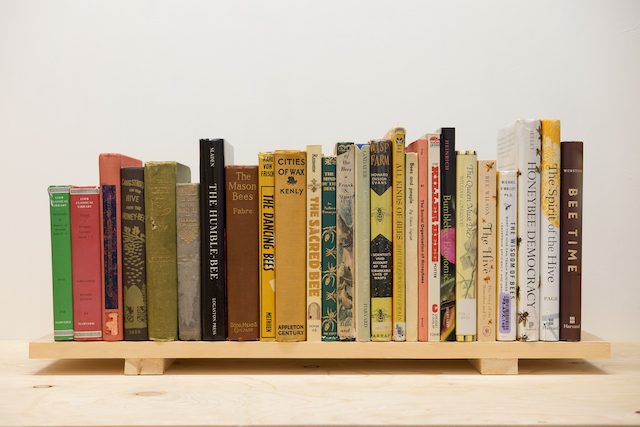

The Political Beekeeper’s Library and Bee Shed are two of the works the artist is showing in Marabouparken. The former is a collection of books where authors from Aristoteles to Thomas D. Seeley draw parallels between bees and humans, in particular how they are socially and politically organized. “What starts as a story of a patriarchal monarchy ends with a tale of radical democracy.” Bee Shed is a sculpture that also functions as a large house for pollinators. The shelter explores what a public park would look like if it was built from the perspective of the wildlife that use the park alongside the humans.

[Reading performance by artist Mia Isabel Edelgart at the bee shed in Marabouparken, Stockholm Sweden, 2018. Photo: Erik Sjödin.]

Here’s what our email exchanges looked like:

Hi Erik! For the Marabouparken, you have created a sculpture that also functions as a house for pollinators. The work questions our understanding of what constitutes a ‘good’, pleasant park and suggests that we might want to interrogate this human-centered perception and think about what a park would be/look like if it were built from the perspective of the wildlife that use the park. Can you then tell us about some of the characteristics and qualities of a park that caters also for non-human living species?

For the Marabou park I have created a bee shed. It is essentially what’s usually called a “bee hotel”, although I’m trying to contrast the transient dwelling and luxury connotations that a hotel has by calling it a shed. In its appearance the structure is humble and resembles a wood shed for storing firewood. A wood shed is a typical structure that is part of the old cultural landscape in Sweden and may provide habitat for many insects and other animal.

The Marabou park was initially landscaped in the beginning of the 20th century with the intent to provide relief for workers at the Marabou factory which is now an art space. Two separate parts of the park were explicitly constructed with inspiration from The Arts and Craft Movement and Functionalism respectively. The arts and craft movement came about in 19th century Britain as a reaction to increased industrialisation and harsh conditions for factory workers. Functionalism emerged in the first half of the 20th century and promoted increased industrialisation and efficiency. Although contradictory both of these design and construction philosophies have in common that they try to provide for the needs of humans. They also have in common that they don’t actively take into account the needs of nonhumans such as animals and plants.

With the bee shed we try to add an element of consideration also for nonhumans in the park. It provides a habitat for solitary bees and other insects. We will also work with the park management to increase the amount of flowering plants in the park, for example in the form of more meadows instead of lawns, and to create more habitats for animals, for example by leaving logs and falling tree branches on the ground for insects to nest in. Since public awareness and interest in biodiversity in cities is increasing this is also something that the park management and the municipality is interested in and already working with.

Increased biodiversity in parks in the form of flowering plants, buzzing bees and chirping birds etc can provide aesthetic pleasure to park residents and be relevant besides from the intrinsic value nonhuman life has. Biodiversity doesn’t have to conflict with human interests. Studies have also shown that the best protection for biodiverse urban areas such as parks and forests is human engagement in them.

You’ve been working a lot with bees over these past few years. Recently, journalists have been writing about insect numbers falling because of pesticides, pollution and loss of habitat. Have you found that the public is sufficiently informed and concerned about the disappearance of the little pollinators?

In Sweden media attention and campaigns from various organisations and public figures have done a lot to increase awareness about pollinators. Recently other species than honey bees, mainly pollinators, have gained media attention and people are becoming more aware that there are many insects that are integral to agriculture and our ecosystems in general. People want to save the bees. In general though I would guess that the interest for insects is marginal and insects are probably still mostly considered an annoyance.

[Our Friends the Pollinators, workshop at Marabouparken, 2018. Photo: Erik Sjödin.]

How much can artists and grassroots movements bring to the emergency to save bees? Can citizens have a real impact on the problem or is the survival of bee populations mostly in the hands of governments and the agro-food industry?

Artists and other citizens and organisations that create awareness help shape public opinion which create incentive for governments to develop policies that allow for farmers and industry to change their practices in ways that increase biodiversity. When many people change their consumption patterns, for example by choosing more ecological and locally produced food and other products, that may also make real difference.

[The Political Beekeeper’s Library at Bildmuseet in Umeå, Sweden 2017. Photo: Erik Sjödin.]

The Political Beekeeper’s Library (a research which you generously share at thepoliticalbeekeeperslibrary.org) looks at books where parallels are drawn between how bees and humans are socially and politically organised. “What starts as a story of a patriarchal monarchy ends with a tale of radical democracy.” Could you explain what you mean by that?

Those are not my own words but it is a fitting and hopeful description of the library as a whole. The library contains books spanning from 4th century BCE when the hive was generally considered as a kingdom, a notion that dominated into the 17th century when the idea of the hive as a monarchy but now with a queen began to emerge. In the 21st century there has been scientific books published which dethrone the queen and describe the beehive as having democratic elements. Radical is a word that is relative but in some contexts the collective decision making methods the bees apply could be described as radical.

As your research shows, bee organisations have been understood in different ways through time. Are the way they function and govern themselves subject to as many interpretations as there are political systems in favour at a certain moment? Or have we, in the 21h century, finally reached an agreement, an objective understanding on how bees are socially organised?

I suspect there isn’t agreement or understanding about all aspects of how bees are socially organised even among scientist such as entomologist and animal behaviourists. However, there are a lot of behaviours that have been independently observed and there is consensus around. In contemporary non-academic but “science based” literature interpretations of the bee society still vary wildly, from the hive being described as a smooth running company with a skilled CEO to the hive being a dystopian totalitarian state.

[The Political Beekeeper’s Library at Losæter, in Oslo, Norway 2017. Photo: Erik Sjödin.]

What lessons could humans draw from the way bees are organised?

I would be careful to apply ideas about how bees are organised onto how humans ought to be organised, but many people have done so. The roman philosopher Seneca for example is said to have been inspired by the poet Virgil’s depiction of the beehive as a kingdom in claiming that monarchy is an invention of nature. Seneca was the teacher of emperor Nero who eventually forced Seneca to take his own life for alleged treason. Perhaps Seneca regretted drawing conclusions from the bees.

Thomas D. Seeley who is the author of Honey Bee Democracy, published in 2010, advocates that humans should learn from the decision method that bees use when they swarm and have to decide for a new place to nest in. However, that decision method, a form of representative quorum sensing, is just one of many more or less democratic decision making methods that are available to us humans.

[Nest for solitary bees made of reed bundled in birch bark, at Marabouparken 2018. Photo: Erik Sjödin.]

Let’s say i’m someone who has access to a balcony or a garden but i don’t want to install a beehive. Is there still something i can do to help bee pop thrive?

Yes. Lawns are great for play and leisure but if you have more lawn than you need then it’s a good idea to convert some of it into meadow or to plant other flowering plants. Bees enjoy flowering herbs for example, which also works great to grow on a balcony. If the balcony is too high up for the bees then at least you have something to spice up your food with. You can also create habitats for wild bees, for example by making dry sand and soil beds for ground nesting mining bees, or by drilling holes of various sizes in old logs for mason bees and leaf cutter bees.

[The Azolla Cooking and Cultivation Project at Agoramania in Paris, France 2018. Photo: Erik Sjödin.]

[Azolla Cultivations at Hauser & Wirth Somerset. Photo: Hauser & Wirth Somerset.]

I think the last time i interviewed you was about The Azolla Cooking and Cultivation Project. That was in 2011 and the work continues to attract interest from art institutions. Has the project evolved and grown since we last talked about it?

It keeps getting more complex and has reached a point where it’s difficult to push some aspects of the project further without proper scientific studies, but I’m still working with it when opportunity arises. Recently I’ve been collaborating with Ségolène Guinard, a philosopher and PhD candidate who has studied space exploration and plants in space. Since Azolla has been proposed as a potential crop for Mars settlement I think it’s valuable to bring her contextualising perspectives into the project. I’ve also participated with an indoor Azolla cultivation in the comprehensive exhibition The Land We Live In – The Land We Left Behind at Hauser & Wirth in Somerset. This gave me some resources and incentive to try new technology for growing Azolla under artificial light. I’ve had some trouble growing Azolla indoors previously but now I have gotten this to work pretty well. If cultivation under artificial light makes sense in general can be questioned, but it enables me to keep the plant growing year around and learn more about it.

[Apiary made of drift wood. In the west fjords, Iceland 2017. Photo: Erik Sjödin.]

Any upcoming project, event or field of research you’d like to share with us?

Currently I’m mainly focusing on research and production of work related to pollinators. Last year I visited beekeepers in Iceland to document their apiaries and try to understand their motivations for keeping bees in Iceland. Beekeeping is not yet established in Iceland and the conditions are not always ideal for beekeeping. Honey bees might also compete with native pollinators for limited floral resources. I’m hoping to maybe go back to Iceland to visit more beekeepers and to connect to researchers who monitors the flora and fauna on Iceland. Eventually I would like to put some effort into presenting the material and research I’ve gathered, which I think paints a complex and both problematic and hopeful picture.

[Apiary in south-west Iceland, 2017. Photo: Erik Sjödin.]

Why would beekeepers want to establish bee colonies in Iceland if the conditions there are, as you noted, not optimal? Do you already have an idea of the motivation of the beekeepers or do you still need to do more research into it?

Why people attempt to keep bees on Iceland is part of what I have been trying to find out. People have been trying since the 1940’s and so far it hasn’t worked out in the long run. There are around a hundred beekeepers on Iceland now, more than ever before. Maybe together they can figure out how to make the bees thrive. Some people are quite successful, although in general they are still dependent on import of bees.

The beekeepers on Iceland are all part of the same community of beekeepers and they import bees from a beekeeper on the island Åland in the Baltic Sea. The reason they import from Åland is because the honey bees there aren’t infested with the dreaded varroa mite. One reason for beekeeping on Iceland that many beekeepers bring up is that if beekeeping is successfully established then Iceland could be another “safe zone” where bees can thrive without the mite.

There’s not much reason to keep bees for the honey. The yields are generally quite small and importing honey is much easier and cheaper. However, although I don’t think people do it just for the money, local honey can be marketed and sold to very high prices on Iceland and this actually makes it a more lucrative business for some than beekeeping is in, for example, Sweden. Some beekeepers hope that honey bees could help with pollination of plants and boost their local flora, but there’s not a real need for pollination of crops. I think generally people keep honey bees simply because they think it’s fun and they would like to have bees around just like they have other domesticated animals. Some people have lived abroad and been beekeepers in for example Norway or Sweden, and they want to continue to keep bees on Iceland too. One beekeeper, an artist, simply said it was for aesthetic reasons, he would like to have bees buzzing around on his farm.

Thanks Erik!