Text: Martha Nicholson, Medicor 2016.

Urban farming is now widely recognised by city planners, academics, public health practitioners and architects alike as part of the solution for a sustainable and reselient future. Here’s a guide on how the practice of urban farming has taken Stockholm by storm, and how to muck in and start farming yourself.

Have people farmed in cities before?

Urban farming is not a new phenomenon. Since the dawn of city life people have grown their own food at times of economic hardship and supply chain disruption. Take wartime Britain for example; in 1917 a home gardening campaign was launched brandishing the mottos “food will win the war” and “dig for victory”. Then there’s the green-fingered allotment and backyard farmers. They grow in pursuit of weekend pleasure and perfect lettuces, but prefer to act alone (not usually seen in groups). These urban farming members have become somewhat of an elite in Stockholm. The rising prices of land and the 10-20 year waiting list for allotment space means not everyone can be part of this exclusive club.

Why start farming now?

Now’s the time for new community initiatives to gain traction in Stockholm. Exciting high-tech ideas have swept through cities with the aim to reduce the distance hydroponics system in Berlin? It’s more or less a highly sophisticated Perspex cube that grows herbs, radishes and greens inside grocery stores with the power of LED lighting and fertilizer. Then there’s the Brooklyn Grange Farm project in New York City which has developed a cultivation network on rooftops and unused space for a “fiscally sustainable model for urban agriculture”.

These cities are making giant leaps in fulfilling Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2.4 which aims to ensure sustainable food production systems and implement resilient agricultural practices”. So what have Stockholm’s residents done to build systemised urban farming? There are lots of exciting projects, but my favourite has to be the renaissance of farming land on the abandoned rail tracks of Södermalm. It’s been built by the community initiative Trädgård på Spåret, or “Garden on Tracks”. Sustained by volunteers and a summertime café, this really is the essence of urban farming. Then we have the home-grown organisation, Plantagon (plantagon.com), a vertical farming initiative that has designed an inner city greenhouse based in Linköping to produce 500 tonnes of crops every year. Construction is due to start in 2016, so watch this space.

[Beekeeping at Eggeby Gård 2015. Photo: Erik Sjödin.]

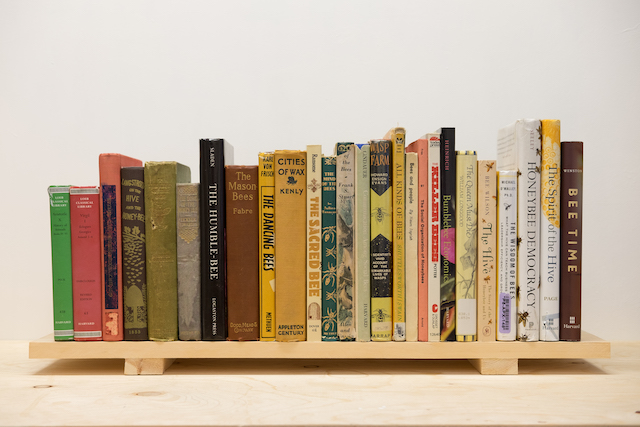

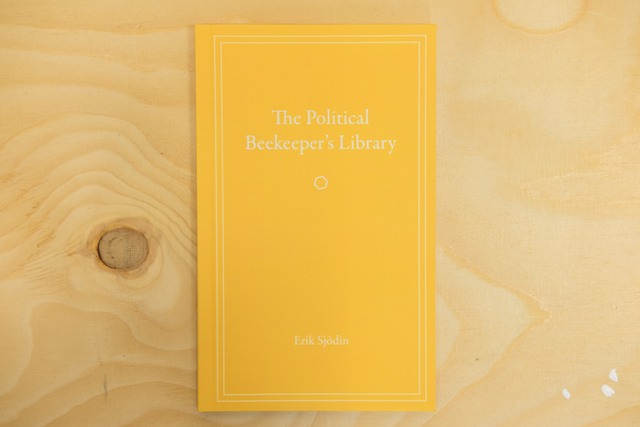

Erik Sjödin

Artist and urban farming researcher Erik Sjödin invited me to his studio in Årsta to discuss the social benefits of the urban farming movement in Stockholm.Having collaborated with farmers in and around Stockholm for over five years, he has seen progress with community initiatives and has campaigned for the protection of green space where it is needed the most. Erik has a portfolio of art and research projects exploring human relationships to bees and growing alternative food sources such as the water fern Azolla.

As we sat in Erik’s studio on a frozen February afternoon (too cold for farming), he was planning a talk on the “Future of Food”, at the Openlab’s Dome of Visions at KTH, which is also a KI collaboration. I wanted to know what his main message to the audience was going to be. Erik explained that in the midst of our citydwelling and consumerist lifestyles, we project our own socially constructed values onto our food. “We are conditioned to seek the perfect shaped vegetables and let the food industry dictate our choices through advertising campaigns for addictive fatty and sugary foods. The food industry is cutting corners on the quality of products to ensure profits. That has to change.” Erik admits that the industry is beginning to adapt to a more producer aware consumer that is interested in eating a diverse, healthy and low-impact vegetarian diet. Erik adds, “so it’s up to us all to check where our food is produced and hold industries accountable.”

Urban farming is an opportunity for us to shift our values as city-dwellers and focus on the process of nurturing plants and rearing animals. This will reduce waste and nurture healthy lifestyles in urban communities. Communal farming creates spaces where you find diverse activities and groups of people coexisting. City planners are on it and are now using these spaces as a tool to break down the barriers between socio-economic, ethnic and age groups, creating a more cohesive society.

Health benefits

Erik told me about some of the therapeutic effects of producing your own food. “It goes without saying that eating fresh produce is good for you, but another benefit to urban farming is the action of getting outside and interacting with other people and the natural world. It is the perfect medium for contact with outside space for people with rehabilitation and care needs. Scientific studies at the Agricultural University of Sweden have shown the mental health benefits to farming, but in a way it’s common sense that having exposure to daylight and being physically active is good for you. There are many community initiatives in and around Stockholm that have used urban farming to help people with health problems such as burnout, depression, or neurodevelopmental disorders. Also, hospital gardens have shown therapeutic effect for people with longterm chronic conditions.”

[Green house at Under tallarna 2015. Photo: Erik Sjödin.]

Getting involved in communal cultivation

So how can we all get involved in this green revolution? It’s simpler than you think. You won’t have to shop around long to find a locally sourced product to buy or an urban farming group to sign up to.

Erik explained: “Urban farming is adapting. Since allotments in the city have long waiting lists and are increasingly expensive to upkeep, we’re seeing a new group of people interested in community action, with collaborations from sociallyaware groups that want to see a greener and more intelligent use of urban space”. With spring just around the corner, why not investigate how you can help with urban farming at an elderly people’s home, school or daycare centre in your community? Alternatively, Erik had four recommendations for volunteer-friendly urban farms and community gardens in and around Stockholm:

Trädgård på Spåret in Södermalm

Vintervikens trädgård in Liljeholmen

Under tallarna near Järna

Hästa gård on Järvafältet near Akalla

Vertical Farming

For the lucky few with access to a rooftop or balcony, the world truly is your cabbage patch. Try growing your own vegetables this spring. Start simple with potatoes, lettuce and tomatoes and very soon you’ll have your own personal harvest. Openlab is running workshops and events throughout 2016 to help beginner farmers develop more sophisticated permaculture techniques. There’s also plenty of online resources to help you make the most of your space, no matter how small, with vertical farming strategies.

Erik described some of the architectural design ideas being factored in when building or renovating apartments. “Architects can make it easier for us to grow crops on balconies by building integrated drainage systems for water and even integrating clever automated watering systems and composting. Providing infrastructure for access to soil and water in public spaces will also facilitate more people to start farming”.

Addressing the challenges that Stockholm will face in the next few years will take more than just urban farming. To sustain a happy and resilient population, we need more than just local harvests and cohesive communities. But what we can do is to shorten the gap between farm and fork, bring communities together with collaborative projects and redesign the perception of the “perfect plate”. We are moving one muddy step at a time in the right direction for a more sustainable future.

[Apple picking at Under tallarna 2015. Photo: Erik Sjödin.]