[This is a Q&A with artist and researcher Erik Sjödin about the study circle Humans and Bees, the exhibition The Political Beekeeper’s Library, the pedagogical project Our Friends The Pollinators, and the never realised multispecies community project The Beekeeping Society. It’s an expanded English translation of a text originally published in the magazine Fält by Art Lab Gnesta 2015.]

[The Political Beekeepers Library at Under tallarna 2015.]

Tell us about the background of The Political Beekeeper’s Library?

The Political Beekeeper’s Library is the result of a nearly five year long process that includes several more or less completed projects that revolve around relationships between humans and bees.

I started to take interest in beekeeping when colony collapse disorder gained media attention in the late 2000s, although my grandfather was a beekeeper and I guess I have always been positive to beekeeping because of that. I was amazed at what large scale and how intensively beekeeping is conducted in many parts of the world. For example in California where at times huge loads of beehives have been shipped in with jet planes from Australia to pollinate almond groves.

In 2010 I received an invitation to do a project together with DKTUS, a platform for contemporary art and artistic research, located in the Old Town in Stockholm on the site that used to be the kitchen garden for the Royal Palace. In response to this I started to sketch on a project called The Beekeeping Society. The idea was to spend a summer building hives for honeybees, creating a garden with flowering fruit trees, vegetables and herbs, a social environment with benches and tables, and a café that would serve locally produced and organic food and drinks. In this environment, we would also have a programme with talks, film screenings, and workshops.

The idea was that The Beekeeping Society would act as focal point for beekeepers, scientist, architects, designers and artists etc. And that when people from different disciplines would meet and activate the place together they would perhaps come up with things that they wouldn’t come up with on their own.

In addition to discussing beekeeping and the wider context that beekeeping is part of today The Beekeeping Society was meant to illustrate how cultural activities may include nonhumans such as animals and plants. To explain this I related to the concepts relational aesthetics and philosophical posthumanism.

Relational aesthetics emerged in the late 90s as a term for art projects that revolve around social activities and in various ways include people as actors and co-creators. Nicolas Bourriaud, the curator who coined the term, defined it as “a set of artistic practices which take as their theoretical and practical point of departure the whole of human relations and their social context, rather than an independent and private space.”

Very briefly put philosophical posthumanism emphasises the roles of nonhumans such as animals, plants and other beings, but also things and concepts. In doing so posthumanist theory challenges dichotomies and hierarchies that tend to be present in the generally human centered contemporary thought. For example posthumanism challenges rigid distinctions between nature and culture, human and animal, man and woman, and man and machine.

When relational aesthetics was topical in contemporary art, there was a lot of debate about which cultural and social groups were included in this type of projects and on what premises. For example, art historian and critic Claire Bishop wrote: “If relational art produces human relations, then the next logical question to ask is what types of relations are being produced, for whom, and why?”. From a posthumanist perspective it’s worth nothing that neither Bourriaud or Bishop mentioned relationships between others than humans and things. Animals, plants and other organisms did not occur in their writings at all. [2]

The idea for The Beekeeping Society was well received and we received some financial support to write a project proposal and got The Swedish Beekeepers Association and Stockholm Resilience Center, as well as several beekeepers, entrepreneurs, architect, designers and artist to backup the project and support a grant application. Unfortunately in the end we didn’t receive funding to carry out the actual project and thus the project was never realised. Instead, I moved to Bergen in Norway to purse an MFA. Partly because it was a possibility for me to continue to work on my own projects with a study grant, but also out of curiosity on being a student at an art school and in a different cultural and geographical environment.

When I moved to Bergen, in autumn 2011, the Occupy Wall Street movement started in New York. I followed the developments with great interest, although I did it remotely, and for me it meant a political awakening.

In Bergen I continued to immerse myself in the humanities, such as philosophy, sociology and anthropology – a direction that I hade taken since I started to pursue my own projects after I stopped working full-time as an employed engineer and researcher. The humanities were also dominant among teachers and guest lecturers at the art school.

[The Political Beekeepers Library at Art Lab Gnesta 2015.]

Eventually I began to sketch on a new project about beekeeping in which these perspectives would be more present. In the new project idea I related to Thomas D. Seeley’s book Honey Bee Democracy which was published in 2010. In the book Seeley describes how honeybees take common decisions when they swarm and choose a new location to settle at. Seeley also mentions that in the research team he leads at Cornell University he uses a decision model built on the same principles as the honeybees.

Inspired by this my idea was to study how beekeeping associations are organized in different parts of

world. Beekeeping associations are often organizations that have been around for many years and have developed effective system for sharing beekeeping equipment and exchanging knowledge between members. I thought this would be interesting to study, and that it might be possible to find parallels or differences between how beekeeping associations and bee societies are organised.

My idea was to build a project around beekeeping societies in Iceland, England and Spain. Three sites in Europe that are culturally and geographically interesting, with both great similarities and differences. England and Spain were also natural choices because I saw opportunities to cooperate with the art organisations Campo Adentro and Grizedale Arts that I had been in contact with before.

In many ways I saw the end result of this project in front of me as an anthropological study, largely built on visual documentation using photography, but also audio and video. To give something back to the beekeeping associations I intended to study I figured that I could introduce them to various books and texts that I have found through my research on beekeeping.

However, after a year in Bergen, I ended up in economic and existential predicaments. Because of this the new project ended up as nothing more than a project description. However, when a project has got a certain substance I find it difficult to just let it go and eventually the idea of The Political Beekeeper’s Library as an independent project formed.

[Our Friends The Pollinators at Eggeby gård 2015.]

Other parts of the original idea of the project The Beekeeping Society have subsequently been implemented in the pedagogical project Our Friends The Pollinators, together with Eggeby gård and Tensta konsthall, as well as with with Hästa gård and Färgfabriken. This past summer (2015) I have for example built beehives, nest sites for solitary bees and nests for bumblebees together with youths at Eggeby gård.

With support from Konstfrämjandet I have conducted the study circle at Under tallarna in Järna. In the study circle, Humans and Bees, we have had a conversation that has departed from books in The Political Beekeeper’s Library as well as academic texts that in various ways discuss relationships between humans and bees. I have also worked with documenting the context in which the study circle has taken place at Under tallarna – in line with the project I sketched on in Bergen.

Because The Political Beekeeper’s Library is presented as an exhibition at Art Lab Gnesta I have been able to acquire more books for the library, which now includes around thirty titles. I have also had the opportunity to spend more time on reading, cataloging, and presenting the books. In other words much has fallen into place this summer.

What questions were raised in the study circle?

In the Humans and Bees study circle we discussed how beekeeping is conducted in the world today and for what purposes. We have for example discussed large-scale beekeeping in the US, where bees are used to maximise economic profit from honey production and for pollination of large monocultures, and beekeeping in a village in England where bees are managed for their own sake and not primarily with the aim of making economic profit. We have also discussed how bees are used for military purposes, and how ideas about race, class, nationality and gender affect how bees are described in various contexts.

In the study circle we have also looked at how bees live and how they can be said to be politically organized. Honeybees are categorized as eusocial animals, which means that they are animals that live in societies where only one or a few individuals handle reproduction, and that there is a division of labor in the society.

When bees swarm and have to take a joint decision on where to settle and form a new society, they use something called “quorum sensing”. Briefly, this means that when a enough individuals, in this case scouting bees, believe that a nest site is good enough according to certain predetermined criteria, such the size of the nest site and the entrance hole, the whole swarm moves there. There is not just one individual, for example the queen, who decides where the swarm will move. But it is not a decision which all bees are involved in or agree on either.

[Humans and Bees, study circle at Under tallarna 2015.]

In the first study circle meeting I presented books in The Political Beekeeper’s Library. These span from History of Animals by Aristotle, from the fourth century BC, to Honeybee Democracy by Thomas D. Seeley from 2010, through, among others, The Feminine Monarchy by Charles Butler from 1609. In the books in the library you can see a clear evolution of how the bee society has been described as having been ruled by a powerful male ruler, to a monarchy with a queen, to something that can be likened to a democracy without a clear leader.

Presenting The Political Beekeeper’s Library in the study circle at Under tallarna has been a great preparation for the exhibition at Art Lab Gnesta. There is quite a lot that is obviously nutty in the literature on bees, that we have talked about in study circle. For example the probably first literary reference to beehives are found in Hesiodos’ Theogonia from the eight century B.C. Archaeologist Eva Crane describes Hesiodos as thoroughly misogynist and mentions that he compared women to drones. Hints of xenophobia and ideas of race can also be found among the books. On the other hand, others have actively resisted against drawing such parallels. For example the Austrian Karl von Frisch who was forced away from the University of Munich because he refused to let Nazi ideology influence his research. Karl von Frisch later received the Nobel Prize for his descriptions of bees individual and social behaviours.

In the study circle we considered how attitudes and ideas change over time, and what perspectives could be found elsewhere, such as in Asian literature, or in oral traditions. We have also discussed many philosophical concepts that we were introduced to in the texts we read; for example Judith Butler’s concept of shared vulnerability and Marcel Mauss’s ideas about gift exchange. In both cases, we considered how these concepts could be extended to include relationship between humans and nonhumans. There is also a lot that we have been introduced to in the texts we read that we haven’t had time to go deeper into, for example Jane Bennet’s “vibrant matter” concept.

How has the discussion been influenced by the location?

The original idea with The Beekeeping Society was to create a space for conversations about relationship between humans and nonhumans, and for encounters between humans and nonhumans. Under tallarna is an existing site that is already better for this than the place I envisioned to build up for The Beekeeping Society.

[Beehive at Under Tallarna 2015.]

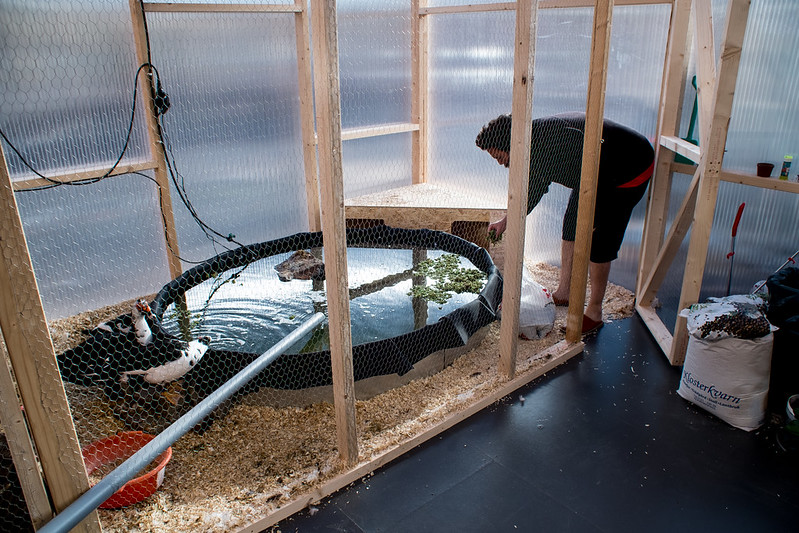

The setting is important for a productive conversation. However really bad ideas can slip down uncritically if they are served in a friendly and cosy environment, but with that said, I feel that it has contributed positively to the discussion that we were able to sit outside under a tree when the sun shined, or in a warm greenhouse when it was raining, and that we have had bees, ducks, chickens, dogs, children, and adults moving around us.

Under tallarna is permeated with intuitive, practical knowledge and doing. Academic discussions have a place there as well, but it feels like words are of less importance. It’s a lot better to be able to demonstrate and study things in practice and not just in theory. It would had been a completely different situation if the study circle had occurred in the city in a place where the participants only could try to imagine a place like Under tallarna.

[1] In 2010 there was still a lot of speculation about what causes colony collapse disorder. Today it’s generally acknowledged that colony collapse disorder is a combination of several environmental factors that stresses bees, and that the most negative factor is a type of pesticides called neonicotinoids. In 2013 the European Union restricted restricted the use of these pesticides in Europe but they are still used in the US and elsewhere. Colony Collapse Disorder is not phenomena in Sweden in the same way as in the US. However there are other problem with beekeeping in Sweden, for example that there are not as many beekeepers as there used to be, and that there’s a decline of flowering plants that the bees can feed on.

[2] Bourriad returned to the relational aesthetics concept as a curator of the Taipei Biennial 2014 through which he sought to “expand on his theory of relational aesthetics, examining how contemporary art expresses this new contract among human beings, animals, plants, machines, products and objects.”